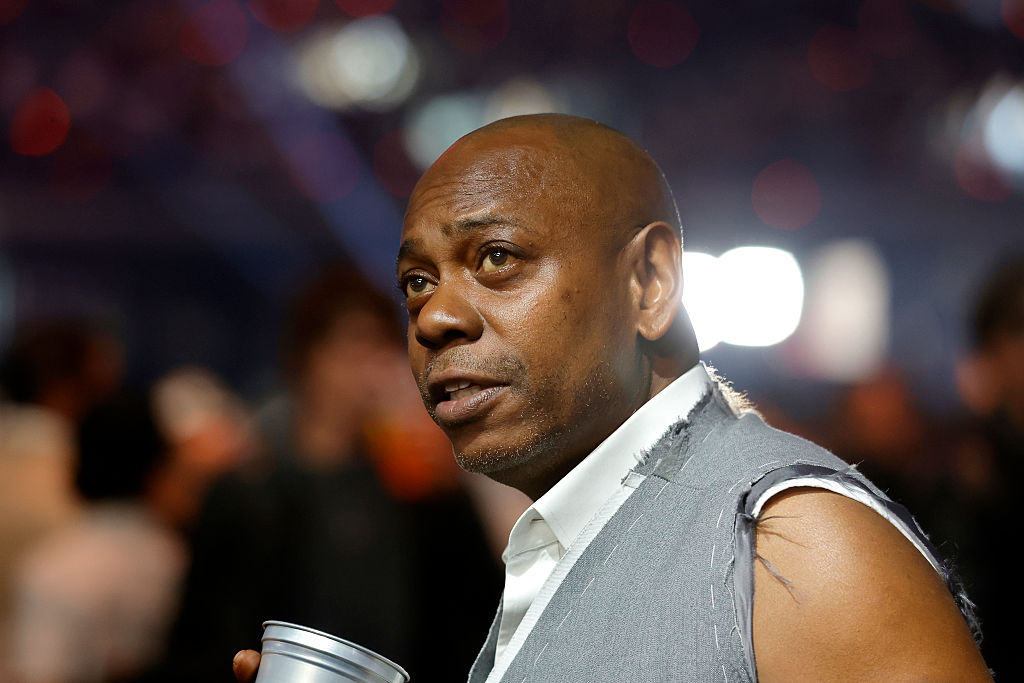

Photography by Jordan Reyes

Patrick Shiroishi approaches sound as a living archive, a vessel that captures fragments of time and lived histories.

With his latest LP, Forgetting Is Violent, Shiroishi refuses to let the history of violence endured by generations of Japanese ancestors be erased. Through distorted textures of ambient and electronic sounds, carried by the breath of his alto saxophone, Shiroishi creates a body of work that feels both intimate and monumental.

The devotion to memory is omnipresent within the details of his works. The cover of Resting in the Heart of Green Shade, released in 2021, features a family photograph of his mother with her brothers and grandmother, a gesture that situates his music within a lineage. With Forgetting Is Violent, he unearths those voices and stories again, but here they emerge with greater urgency, as if to insist that remembrance is not only sacred but necessary.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Over the course of several years, Forgetting Is Violent grew from small seeds of ideas into a vivid collection that carries the fullness of Shiroishi’s artistry. This passage of time allowed him to widen his lens of reflection, shifting from his personal history to incorporate that of the collective. As he explains to me, “A lot of the [past] records, like Hidemi, [took] a very micro look into my grandfather’s experience in the concentration camps. Descension was when Trump got elected and I couldn’t believe it. Evergreen is based on the cemetery that my family is buried in and it was a moment of me connecting with that.”

The album is spread across eight tracks and divided into two suites, the first movement contemplating the harrowing effects of racism and the patterns of injustice that are inflicted on migrant communities and people of colour. The last suite, comprised of four tracks, is framed as a meditation on grief. Confronting the loss of a family member to overdose, Shiroishi composes from the vantage point of what lingers after loss, and these personal and collective experiences are inseparable: “Both those things tie into the idea that forgetting is a violent act – whether it be the racist shit or people forgetting about the camps and then Trump rebuilding on the same land that Japanese-Americans were held on, or family members that have passed away,” Shiroishi tells me.

Forgetting Is Violent reveals Shiroishi’s constant reckoning with memory, but he points out that it is not something he deliberately summons to the surface. Rather than consciously reaching back into the past, his music functions more as a space for emotional processing.

“I think I’d be a very different person if I didn’t have music,” he says, “because that’s my way to process and sit through the emotions. Some of the [live] set can be very loud and distorted, depending on the situation, and it acts as a way where I could release that into the world instead of keeping it in.” From the outset, Shiroishi commands attention with the opener, “To Protect Our Family Names”. A Japanese woman recounts the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, her words looped and layered until they form a haunting chorus. Shiroishi enters against this backdrop with rapid stabs on his saxophone, creating a distress signal that cuts through the weight of history.

“I love how, even if you don’t know what she’s saying, you can hear what she means,” he says. “It creates this anxiety beginning and it was a very intentional way to start instead of here’s my saxophone, here we go, you know me for this.” The piercing ring of a guitar bleeds into the following track, “Mountains That Take Wing”, where Shiroishi’s horn eventually settles into a softer melody, yet beneath it lies a constant interplay between harshness and subtlety, textures dissolving and colliding in turn. Arriving like a gust of wind, Shiroishi’s voice soars over the bed of instrumentation and reveals a new dimension to his brilliance, one that is charged with raw feeling.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

With this project, he offers a mountainous view of the composer he has become, stepping away from rigid modes of expression. He explains: “With some of the other records, it’s very ‘this’. It’s very saxophone with distortion; it’s field recording–based; it’s quartets, trios, and short pieces together – but [Forgetting Is Violent] stems from a lot of stuff and is a full picture of what I’m tryna do.”

For the first time, Shiroishi invites a selection of close friends to contribute intentional layers to the album, while maintaining a sense of fluidity that means its overall identity is free from gaps or interruptions. This stage came later in the writing process and he granted each collaborator the freedom to interpret the existing sounds. Within the first suite, Aaron Taylor speaks through the electric guitar on “…What Does Anyone Want But To Feel A Little More Free”, although he was initially tasked with adding vocal layers. Shiroishi recalls his reaction: “At first I was like, ‘What, what is this?’ and I almost replied, but I thought, ‘Okay, I trust this man – let me just chill out for a little bit and sit with it.’ I let a week go by and realised he had made the track stronger.”

Taylor’s instinctive choice left space for Shiroishi to stitch in the voice of his aunt and activist Jo Ann Shiroishi, who speaks of her early encounters with racism in America. In the final moments of this first suite, her testimony ends with a plea to continue speaking out against racism, "because if you don’t then [it] becomes a crippling poison”.

From here, we are lulled into the second suite that opens with “There Is No Moment In Life In Which This Is Not Happening”. It was the last piece Shiroishi composed and he describes it as a transitional moment, where he centres his voice like never before. Layering field recordings with Japanese language singing, he turns to questions of identity in a tone of lament. There is a profound sorrow in the way he shifts octaves along the main vocal line, his voice wailing over soft layers of stacked harmonies. It’s a delivery he frames as deeply tied to language and vulnerability.

“As of right now I’m only singing in Japanese because I feel comfortable that way, maybe in the fact that not everyone can understand what I’m saying,” he shares. “You don’t have to necessarily understand the words that are coming out of my mouth but you will understand what I’m trying to say, on a human level.”

Part of the humanity he expresses here lies in his refusal to strive for perfection; his decision to foreground his voice stands as testament to that shift. After years of sharpening his agility and range on the saxophone – both as a solo musician and as a member of the progressive rock outfit Upsilon Acrux – he returns to his first instrument: the voice. Reflecting on this, he tells me, “I’m always searching for how I can expand my sound because so much has been done with the saxophone already. It’s very scary not being a singer and it’s a work in progress for sure, but it allows me to vocally express something.”

There is an unmistakable clarity in Shiroishi’s creative choices here, where moments of silence and the trace of a breath are valued as much as the densest beds of instrumentation. He invites listeners to rethink conventional notions of listening, especially in tracks where dynamic arrangements are not always present, allowing what brews in the silence to stir within. Shiroishi reflects on his early days as a musician, when filling every gap with elaborate motifs was the goal for most emerging instrumentalists, despite the risk of obscuring the message. Engaging with traditional Japanese music taught him the value of silence.

Of the project, he admits, “[These silences] may make the listener uncomfortable, but it’s very vital. It’s another decision I wouldn’t have made 5–10 years ago. Now I’m starting to care a little bit less about that and more like, what am I trying to say?.”

Accompanying Forgetting Is Violent are liner notes, written by Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Hua Hsu, alongside a small zine titled Tangled, created in collaboration with other Asian-American artists. It features a collection of poetry, essays, and short stories and is Shiroishi’s way of exploring what lingers beyond the sound, preserving the after-effects of creating an album. This is the third edition of its kind and acts as both a communal space and an archival gesture to bring together voices and perspectives that reflect the Asian-American experience.

When settling into Forgetting Is Violent, Shiroishi encourages listeners to create a space for deep and embodied listening. “I hope that their first listen is straight through, maybe with the lights a little low,” he insists. This body of work demands such focus because it positions Shiroishi as a musical historian, collecting the experiences of his direct lineage, the communities he is connected to, while processing his journey through grief and the unfolding of his Japanese-American identity in the context of violence and erasure.

Forgetting Is Violent is released 19 September via American Dreams Records

1 month ago

42

1 month ago

42

English (US) ·

English (US) ·