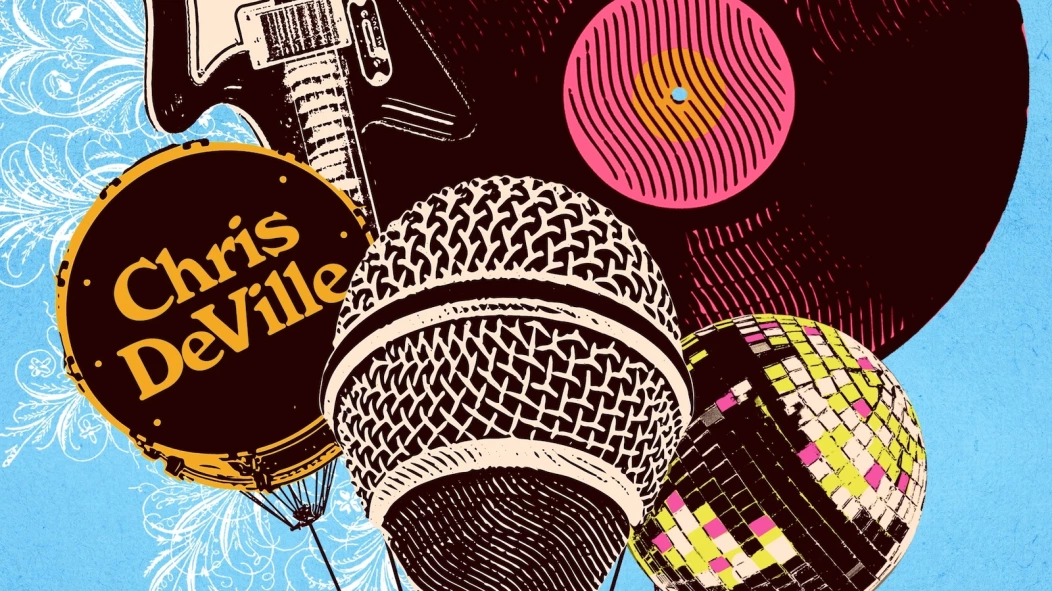

The recent stomp clap discourse sparked a lot of conversations about how the divisive 2010s subgenre grew out of 2000s indie-folk, and the evolution (and “gentrification”) of the latter is actually something that Stereogum managing editor Chris DeVille tackles in his upcoming book Such Great Heights: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion, which comes out this Tuesday (8/26) via St. Martin’s Press. Ahead of its release, we’re bringing you an excerpt on how freak folk made way for something that eventually made its way to the masses.

Pre-order Such Great Heights and find more info on the book here.

**

It wasn’t long before the scraggly hippie vibes of freak folk gave way to something more sanitized, scalable, and twee. When I say “twee” here, I mean it in the broader Merriam-Webster sense of “affectedly or excessively dainty, delicate, cute, or quaint,” not the more specific musical subgenre known for its proudly amateurish qualities. Because there was nothing amateurish about the indie folk that began to arise in the second half of the aughts and on into the early 2010s. As so often happens, a vibrant subculture was transforming into something more like a product—not always a sterile product, but certainly a product more accessible to a normie audience. If freak folk was like a local vegan co-op, the stuff that followed was Whole Foods.

Stevens, with his meek narration and co-ed chorales and ostentatious orchestrations, had something to do with that change. So did the Decemberists, who signed to a major label and kept indulging their most precious theater-geek tendencies, even acting out a maritime battle with a whale onstage at Pitchfork Music Festival. The edgeless indie balladry propagated by Hollywood and Starbucks played a role, as did a swarm of quirky blog-rock bands with a dozen members and a brass section. And acts like Beirut (sort of a Neutral Milk Youth Hostel) and Andrew Bird (a whistler and violist formerly from Squirrel Nut Zippers) injected a fancy baroque pop element into the scene.

Not every new act in this sphere was smoothing out its music. Bands like New York’s Gang Gang Dance were still delving into druggy, tribal sounds at the outskirts of polite society. The artist now known as Anohni was applying her peerless voice to cabaret- ready balladry with assists from artists like Devendra Banhart and Lou Reed. Two years after Golden Apples, newer freak-folk artists like New England’s Feathers and NorCal’s Brightblack Morning Light were still emanating trippy vibes. But the iconoclasts’ reach was far exceeded by the likes of José González, a Swedish singer-songwriter whose crystalline acoustic cover of the Knife’s indie synth jam “Heartbeats” became a coffeehouse sensation.

There were a lot of catalysts and reference points for this more streamlined indie-folk sound, not all of them strictly musical. The rise of the fussy, meticulous, unflinchingly precious film- maker Wes Anderson was a helpful parallel—and not just be- cause Team Zissou’s hats looked like something you might see on the guy at the house party with an acoustic guitar, desperately seeking people’s attention while strumming Damien Rice songs. After The O.C. and Garden State and Grey’s Anatomy came Once, a 2007 indie movie musical in which musicians Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová play buskers who briefly find creative in- spiration and romance. Once became a sleeper hit, and Hansard and Irglová—who fell in love in real life for a while, too—toured the world performing songs from the film under the name the Swell Season.

Also illuminating was the spread of publications like The Believer, Dave Eggers’s literary magazine for and by would-be Wes Anderson characters, devoted to “the concept of the inherent Good.” But perhaps nothing captured the spirit of this movement better than Paste, an Atlanta-based music mag focused on adult alternative and Americana, which began carving out a softer, friendlier, less esoteric indie canon than the cred-obsessed Pitchfork. There was some great writing in Paste, but it’s hard to imagine many of the artists it championed being celebrated in a photocopied zine. What’s easy to imagine is someone paging through an issue of Paste at their local coffee shop, where many of the albums discussed on the page might be circulating in the background.

Coffee shops and soft, pretty indie folk were made for each other. Many such establishments hosted open mic nights, but be- yond that, these spaces were set up to become the favored haunts of young city-dwelling music fans. In the ’90s, the rapid expansion of Starbucks and the massive popularity of Friends made coffee shops an avatar of the urbanite lifestyle—a place where college students could gather to sip lattes and socialize while pre- tending to do their homework. Many coffee shops were set up for those gatherings, full of couches and large upholstered chairs fit for sinking into for hours at a time. In a 2024 Dwell article, aesthetics expert Evan Collins described the vibe as “javacore,” typified by “faux-worn furniture, brushed paint on a dresser, French country vibes, lots of flowers . . . found furniture, a thrift shop aesthetic.”

If you ever planted yourself in one of these businesses, per- haps your visit was soundtracked by a mix of acoustic singer- songwriters whose music leant itself to the cozy environs. More than a few Iron & Wine converts were made that way. As the 2000s progressed, advancements in technology made these kinds of spaces even more popular, both for Central Perk-style group hangouts and for hours frittered away in isolation. It was not uncommon to happen upon a hipster brooding in a corner, scribbling in a journal or perusing a novel while listening to their iPod. Midway through the decade, laptops began to outsell desktop computers as the advent of public Wi-Fi revolutionized the ability to get work done (or procrastinate) at a boutique café.

This was all happening in the long tail of 9/11, at the height of George W. Bush’s Iraq War, and one thing freak folk offered was a sense of escapism. Bunyan speculated as much in 2004, telling The New York Times, “It’s a particularly difficult time to look at the world, and maybe right now it’s just easier to create your own.” Although Banhart and his peers were inspired by their elders, their sensibility diverged from more conventional approaches to folk music, which were focused on traditional songs to be passed down. Indie folk was less about connecting with an ancient lineage and more about dealing with heavy emotions by disappearing into highly stylized worlds, full of not just outlandish characters but small-batch wares that connoted high quality and good taste.

But trend-sniffing companies tend to find ways to mass- produce even the most bespoke products, and just as trucker hats had quickly gone mainstream, freak folk’s return-to-Eden vibe was quickly converted into something cute you could pick up from Urban Outfitters. The culture described on the back of Marc Spitz’s book Twee was starting to congeal: “Artisanal chocolate. Mustaches. Locally sourced vegetables. Etsy. Birds. Flea markets. Cult films. Horn rimmed glasses.” Music remained a huge part of that lifestyle, but like the fashion and the food, the sound of indie folk was gentrifying into something more clean-cut.

As roots-rock visionaries like Wilco and My Morning Jacket stepped from the avant-garde into jam-band territory and newer, more put-together artists like Paste favorites She & Him and the Avett Brothers emerged to grab the baton from the freaks, some previously fringy or chaotic musicians were also finding ways to fit into this quaint new paradigm. Even former teenage prodigy Conor Oberst—whose singer-songwriter-y indie band Bright Eyes had been messy and combustible enough to some- times qualify as emo, and who preferred confrontational protest songs like “When the President Talks to God” over a retreat into fantasy—cleaned up his sound for 2005’s tremendous I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning.

In Bright Eyes’ case, shaving off some of the rough edges was not a problem. Released the same day as the less fondly remembered electronic experiment Digital Ash from a Digital Urn, I’m Wide Awake contained some of Oberst’s most mature, in- spired songwriting, including “First Day of My Life,” an instant romantic mixtape staple that coincidentally became the first dance at my wedding and my drummer’s wedding. More than ever before, the album seasoned Oberst’s music with elements of folk and country; he even wrangled some backing vocals from country-rock icon Emmylou Harris. The resulting master- piece set Oberst on a course toward the lucrative world of NPR- friendly adult alternative—a trajectory matched by his Saddle Creek peer Jenny Lewis of Rilo Kiley on her 2006 solo debut Rabbit Fur Coat, a highly enjoyable album of folk rock, soul, and country dismissed by Pitchfork as “indie-yuppie” music.

Iron & Wine broke out the electric guitars on 2007’s The Shepherd’s Dog and shifted their live show toward mirage-like full-band jams. I went to see them on that tour, and I hated how far Sam Beam had drifted from the intimate singer-songwriter fare of The Creek Drank the Cradle. If Beam’s music was starting to seem less alternative, less unique, less special, so was his audience. Observing an outdoor Iron & Wine show in Brooklyn for her 2008 book It Still Moves, the esteemed critic Amanda Petrusich described the trendy neighborhoods around the venue, where “dirty vinyl siding and rusted tin awnings are reminders of a past that’s been consumed and commodified by the present.” After purchasing an ice cream cone amidst booths for local breweries and eateries, she noticed versions of the same hipster uniform everywhere: “star tattoos, oversized sunglasses, studded belts, canvas bags with woodland animals (squirrels, deer, and finches especially) patched in place, scads of rubber bracelets, American Apparel T-shirts, too much jewelry, choppy haircuts, skinny waists.”

The bags emblazoned with forest creatures feel especially relevant to that moment’s prevailing sensibility. In the most famous sketch from the hipster-skewering comedy series Portlandia, SNL’s Fred Armisen and Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein urge a shopkeeper to put a bird on every item in her inventory but are terrified when an actual bird flies into the store. “I remember going around to little boutiques in Portland, and I felt like it was kind of an insult to my intelligence that just because there was a lampshade with a bird stencil on it, that somehow elevated it to a place of art,” Brownstein later told EW. “There was a craft explosion, and birds did seem like a shorthand: ‘This isn’t your average piece of paper—this is stationery now.’”

By the time Portlandia premiered in 2011, the public was eminently familiar with this aesthetic. Maybe this lifestyle was not, as Twee author Spitz asserted, “the first strong, diverse, and wildly influential youth movement since Punk in the ’70s and Hip Hop in the ’80s”—your average person knows what punk and hip-hop are and, I assure you, has no idea what twee means. Yet there’s no doubt that this precious point of view came to prominence as the 2000s rolled on, morphing the sound of folk rock as it collided with the rustic and rugged.

It didn’t get much woodsier than Fleet Foxes, who rocked the requisite facial hair, frequently sang about the great outdoors (trees, mountains, snow, the sun), and slathered their music in vocal harmonies that seemed to echo down through majestic valleys. And, oh yeah, that band name.

Suburban Seattle natives Robin Pecknold and Skyler Skjelset formed the group in their early twenties based on their shared love of retro touchstones like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and Brian Wilson. “Fleet Foxes seem to have stepped right out of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, circa 1967,” The Seattle Times declared in an early writeup, in which Pecknold admitted to asking his bandmates if they could sound more like Crosby, Stills & Nash. You can hear that influence loud and clear on songs like expansive slo-mo ballad “Blue Ridge Mountains” and the urgent “Ragged Wood”—driven onward by a rolling drumbeat from Josh Tillman, who’d later go solo as Father John Misty and become one of indie music’s main characters.

Those kinds of harmonious acoustic anthems were a bit sweeter and smoother than the median indie-folk acts had been kicking out, but Fleet Foxes struck a chord with seemingly everyone they encountered. Phil Ek—who’d produced classics by Pacific Northwest indie royalty like Built to Spill, Modest Mouse, and the Shins—caught wind of Fleet Foxes and offered to record their demo. They signed to Seattle indie standard-bearer Sub Pop and kept piling up accolades. In a four-star review of their self-titled debut album, Rolling Stone hilariously called them “a lower-dosage Animal Collective.” EW bestowed the album with a perfect 10, while Pitchfork awarded Best New Music to both the LP and Fleet Foxes’ introductory Sun Giant EP. By the end of the year, the site had named Fleet Foxes and Sun Giant collectively as the best album of 2008.

Fleet Foxes’ big win suggested millennial tastemakers were now comfortable with loving the same new bands as their boomer parents—or in other words, that the taste gap between Pitchfork and Rolling Stone was growing smaller. Songs like “White Winter Hymnal,” with its crisscrossing vocal melodies and pastoral wordless flourishes, and “He Doesn’t Know Why,” with its overwhelming blasts of harmony, were too potent to write off as pure nostalgia, even if nostalgia was baked into the band’s DNA. Fleet Foxes were triumphant right out of the gate, and they’ve continued to be a big deal—yet they still aren’t even the biggest indie-folk success story of their era.

**

As for who was? You'll just have to pre-order Such Great Heights to find out. Also catch Chris on tour, including an event at Brooklyn's Powerhouse Arena on Monday (8/25). Chris will be in conversation with Jason Lipshutz and there's also a signing and audience Q&A. That goes from 7-9 PM. All tour dates here.

Chris DeVille by Stephanie Lehnert

20 hours ago

4

20 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·